Not a few eyes have glazed over with a puzzled and frustrated look at the use of Latin in the modern Roman Mass or as many call it, the Novus Ordo. “Can this be done? How come you’re mixing the Old Mass and the New Mass?” Well, Latin is hardly the difference between the two! But, I digress. Prescinding for a moment on all of the historical reasons and whys and documents that accompany the Church’s current teaching on the use of Latin at Mass (which would surprise many and convince few), I thought to take another approach first.

In the Book of Genesis, the Tower of Babel was a punishment for the people’s pride—God divided the world into many languages. At Pentecost, God the Holy Spirit descended and gave the Apostles the Gift of Tongues so that all could understand one another and the Faith could be intelligible. Why, then, would the Church promote a so-called “dead language” with which to worship God? Is it to fool people? Or is it some sort of hocus pocus magic trick that the priest does and which no one else can ever understand? (I’m referencing an anti-Catholic phrase in the last sentence that criticized us for our Mass ritual of the past).

As Catholics, we view the world as moderate realists. This means, in one simple sentence, that reality exists, that categories of things exist—apart from the meaning that we may assign to them as humans. For example, whether you believe in it or not, the Real Presence of Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament exists. It is not dependent on our understanding or even our personal belief for it to exist. Contrast this with nominalism—things only have inherent meaning insofar as they are assigned a meaning or given an arbitrary title by us. There are no universal categories, no universal reality apart from us assigning meaning. Why am I talking about this? Well, because the main argument I hear about the use of the Latin language is that “I don’t understand it.” Which means to say, because I personally don’t understand it, it must not have or express an inherent meaning. But for we who believe in reality and in the meaning of objects and things apart from what we assign to them in our time and in our minds, it absolutely makes a difference.

When Jesus tells His disciples to ask and you will receive, knock and the door will be opened[1], He literally means it. He doesn’t mean to ask generally or in a round-about way, but very precisely. The Latin language is precise. It is far more precise than a modern language such as English that is in constant flux and whose meanings and words change for every generation. We experience this lack of precision all of the time in the English Bible—things don’t always add up to the original Greek meaning which is far more nuanced and actually changes the meaning or context. It is no mystery why God, in His providence, influenced the Church to keep one language for communication and public, liturgical prayer—so that His teachings wouldn’t be confused or lack precision; there would always be one official version.

When we gather at Mass, we have a view of time that is different than that of Protestant-based Christianity which relegates time to the group that is present for worship. For the Apostolic Christian, we are present at the court of Heaven. We participate in a ceremony that is not tailor-made to our specifications, our likes, dislikes, or our age, but something that stands on its own—something that is timeless! Something that speaks of...eternity and is outside our own current cultural norm or comfort zone.

When people say that they must understand everything, it gives a false sense of God. That might seem like a bold statement at first, but allow me to explain. God, in His essence, is not understandable in the human intellect—St. Augustine once famously said If we think we understand it completely, it’s not God! But the real reason, in addition to many, is that the words of the Church, handed down century after century have an inherent meaning apart from our understanding. Our personal comprehension is not necessary for worship to be rendered to God. That does not mean we “babble like the pagans do” or have weird incantations which are unintelligible. The use of Latin can have the opposite effect if one lets it—rather than a so-called immediate understanding of the text without spiritually comprehending it, it causes the believer to enter into the mystery that is taking place and to contemplate what the words mean with the help of a worship aid.

The Second Vatican Council actually taught that the use of the Latin language was to be retained at Holy Mass[2]—obviously, it was dropped wholesale and ditched completely in the last 50 years which leaves us, sadly, without ANY understanding of our way of public prayer. In fact, for most, the language of the Church (whose sounds and cadences should be familiar and feel like home) have become alien to the Roman Catholic and make one feel cold, or indifferent. The over-use of the vernacular in the Mass has also had this same effect—how many times did Spanish speakers skip Sunday Mass because they “didn’t understand English” or vice-versa when an English Mass was unavailable?

From a Christian standpoint, ecclesiastical Latin is sacred—along with Greek and Hebrew. The language itself was consecrated when it was written on the cross (think, INRI) which is why it has a particular power especially against things demonic. It is also a hieratic language, one just like Hebrew for the Jews or Arabic for Muslims, or Sanskrit for Hindus that stands apart from everyday common use. Even when Latin was spoken as the common language, Church Latin was not the everyday tongue. While other liturgical rites such as the Greeks, for example, use the language of the people, the Latin Church retained her cross-cultural and cross-temporal bond of faith by maintaining one single “church language.” No matter where one went, what language one spoke, Mass would be familiar—we are all one family. I experienced this years ago serving a private Mass at St. Peter’s in Rome with a French priest and an Italian seminarian—we all knew how to respond, even in our own accents!

It is hard to have a love of something we don’t immediately understand/comprehend, but what sounds foreign to our post-conciliar experience at Mass is actually what binds us to the saints and the long-standing history of our Church. The things of God are NOT readily visible, accessible, understandable, relatable. They should make us strive to enter into His mystery more. If the things of God become any of the above, they become common, and thus boring—why worship if it looks the same as any other conversation we have in life? To hear the same words, the same melodies that St. Benedict, St. Theresa of Avila or even St. Padre Pio heard; to experience the same heritage of our great-great grandparents is the gift of Tradition and the Church. Time moves on, but the language of the Mass stands still.

[1] Matt. 7:7 Fr. Chad Ripperger, FSSP has used this example numerous times when discussing the Latin language and its precision.

[2] Sacrosanctum concilium, 36. The Second Ecumenical Vatican Council.

More News...

St. Ann Feast Day Homily

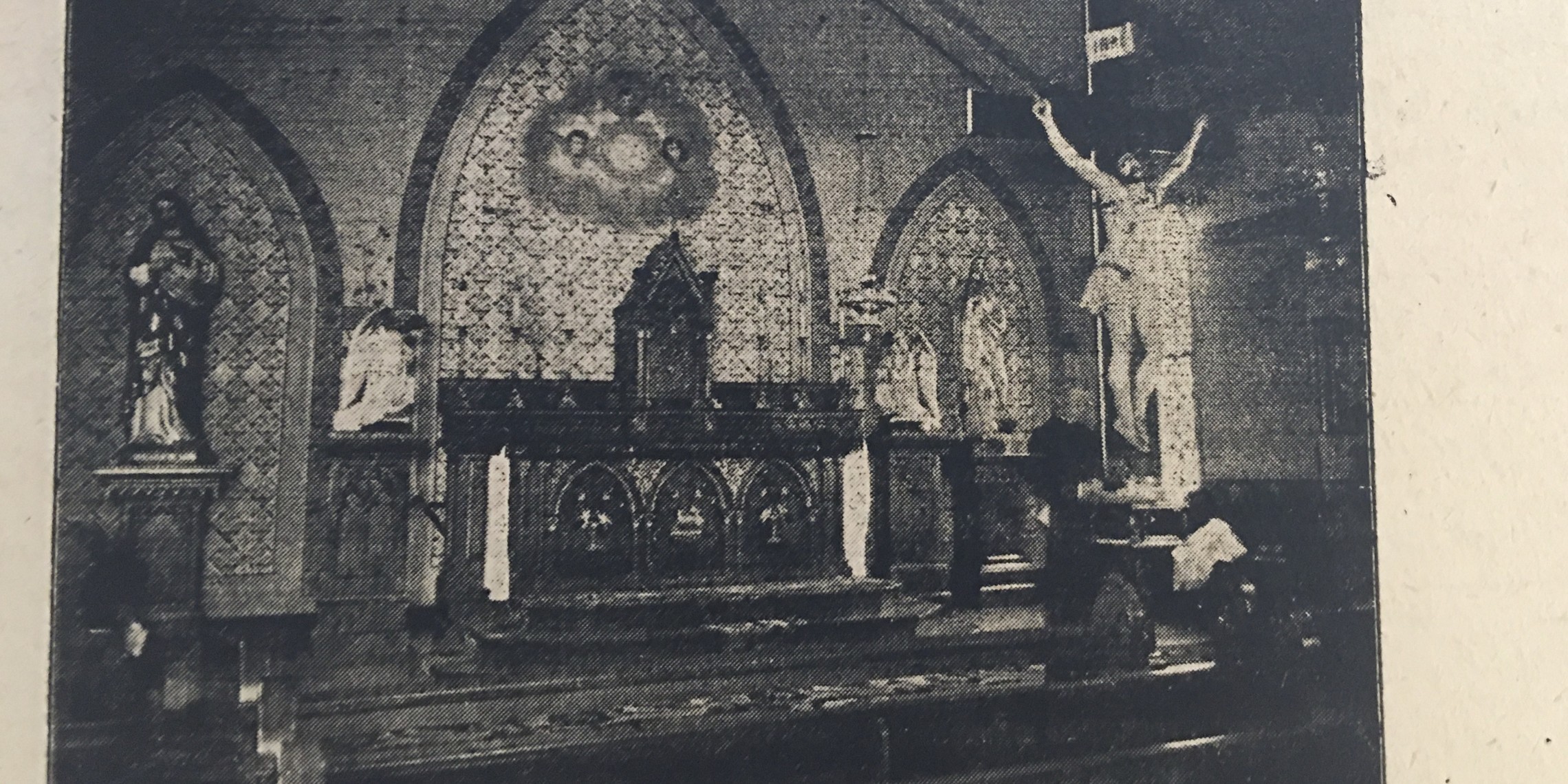

When the Irish immigrants arrived in our town over 150 years ago, they were fraught not only with being outsiders by culture in a...Read more

Forty Hours Devotion

Dear Friends in Christ,

Part of any spiritually flourishing parish is a devotion to the Blessed Sacrament, the Lord’s Eucharistic Presence...Read more